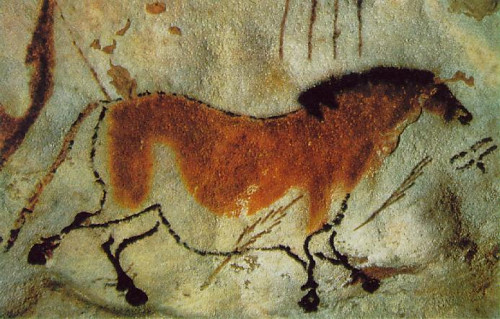

Brandon Keim, who is part of Wired's ace science writing crew also keeps a blog, Earthlab Notes, where he recently put this nice post on The Language of Horses:

In a few slender leg bones and fragments of milk-stained pottery, archaeologists recently found evidence of one of the more important developments in human history: the domestication of horses.Unearthed from a windswept plain in Kazakhstan, the remains were about 5500 years old, and suggested that a nomadic people now called the Botai had learned to ride a creature that had captured mankind's imagination thousands of years earlier.

A passage later in this post made me think of a moment this afternoon, when I took a break from work and sat a while with my wife in our small garden. She had her garden map out -- a lovely hand-drawn bit of work -- and was identifying the bulbs she'd put in last fall and which were now coming up. I'd been immersed in digital representations of the world all morning, and had actually to make myself put down my iPhone on this fine June-day-in-April and look at (if not smell) the flowers. Hearing her say the names of the new plants gave me goosebumps.

Similarly Keim considers the language of horses that rose as we domesticated them:

"Our awe in [the horses'] presence," wrote John Jeremiah Sullivan in Horseman, Pass By , "is as old as anything we can call ours."Little wonder, then, that between primal fascination, the success of mounted warriors and the appreciation of farmers, our language should contain such a rich equine vocabulary.

To describe age and sex, there are males and stallions; colts, foals and fillies; mustangs and broncos and greenbrokes and geldings. They come in roan and palomino coats, piebald and dapple, chestnut or dun, medicine hat and pinto and war shield. They can gallop and trot, canter, lope, forge; have fetlocks and forelocks, hocks and coffin bones, gaskins and pasterns; fall victim to azoturia and spavin, fistulous or mutton withers, lockjaw, moon-blindness.

Such wonderful words, the linguistic equivalent of old farm tools whose purpose eludes modern eyes, but are obviously well-made. Many words derived from humanity's long experience from the natural world possess this quality. Take the words recently removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary: beaver, otter, magpie and minnow; dandelion and ivy; willow, sycamore and acorn; liquorice and marzipan; saint, devil, dwarf and goblin.

In their place we get blog, MP3, voicemail, database, chatroom, celebrity, biodegradable, block graph. The dictionary's publishers explain that children are more likely to encounter these words in everyday life. With some exceptions, they're almost certainly right. Still, I can't help hoping that a shipment of Oxford Junior Dictionaries someday sinks in the horse latitudes .

I write on science, medicine, nature, culture and other matters for the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Slate, National Geographic, Scientific American Mind, and other publications. (Find

I write on science, medicine, nature, culture and other matters for the New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Slate, National Geographic, Scientific American Mind, and other publications. (Find

Comments

Seems they took a lot more words out than they put in. Also, I don't understand the Christian angle (as noted in the article linked) to some very useful words like "blackberry".

Posted by: Donna B. | April 29, 2009 12:09 AM